Click Here if you prefer the audio version.

Subscribe on iTunes

If you are thinking of investing in a complex structured deal and you are wondering who is most likely to bear the greatest risk and costs, it is probably you. The richest people on Wall Street are not necessarily the best investors, but the best deal makers. They are experts at structuring heads I win, tails you lose deals, where the financial success of their investors has little to no bearing on their own financial rewards.

Most financial deals that overwhelmingly favor the party that structures and sells them are usually complex by design, think of complexity in this instance as a feature, not a bug. Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (“SPACs”) are extremely complex and have historically been highly efficient wealth destroyers for retail investors. Complexity obfuscates the risks and costs investors will bear, which is advantageous for any sponsor selling a SPAC offering and potentially detrimental for would be investors that have not done their research.

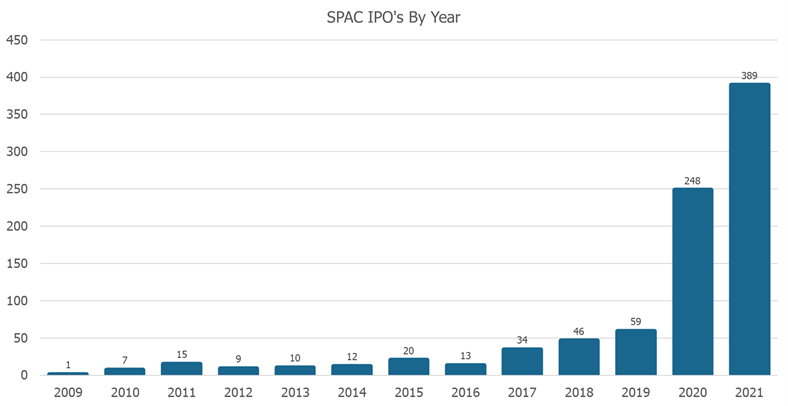

SPACs once occupied an obscure corner of the market, but over the last two years they have entered the mainstream and exploded in popularity among retail investors. Last year, SPACs made up about 50% of all IPO (initial public offering) activity…an amazing number. To further illustrate the growth in SPAC offerings, in 2009 there was one SPAC IPO and so far in the first seven months of 2021 there have been 389 SPAC IPOs.

Source: SPAC Insider

SPACs are exhibit A in information asymmetry between Wall Street and retail investors. To level the information playing field we are going to explain what SPACs are, how they work and why any investor considering buying SPAC shares should proceed with extreme caution.

What is a SPAC?

A SPAC is a publicly traded shell company incorporated by a sponsor (usually a well-known investor, former CEO or private equity firm) that raises capital through an initial public offering (IPO) with the purpose of merging with a yet to be identified private company, thereby taking the private company public. Investors in a SPAC IPO do not know what they are buying when they initially invest, which is why SPACs are often referred to as ‘blank check companies’. Once the sponsor has registered a corporation and then raised assets by taking the shell company public with an IPO, they have two years to identify a private target company and complete a merger.

To summarize…a well-known rich person offers to sell you shares in a shell company so they can try to locate and merge with a yet to be identified private company within the next two years. That is a SPAC in a nutshell…sounds pretty good, right!? Let’s find out.

How a SPAC works

To further our SPAC discussion, it is important to have a general understanding of how a SPAC transaction works. There are three main stages in the life of a SPAC.

Phase 1: Incorporation and IPO

In this stage the SPAC sponsor creates a shell corporation and takes the shell company public through a unit offering, selling each share at $10 with usually one warrant attached to sweeten the deal and compensate initial investors for parking their money for as long two years. A warrant is simply an option to buy common stock in the post-merger company at a specified exercise price. Each warrant is generally convertible to between a half or one share at an exercise price of $11.50 post-merger. Warrants can therefore become very valuable if the share price of the post-merger company increases in value after the merger. Warrants become important later so we will revisit them.

Finally, the capital raised through the SPAC IPO is put in a trust and invested in safe securities like treasury bonds. As compensation for setting up the SPAC and searching for a company to merge with the sponsor purchases 20% of the total equity raised by the SPAC for a de minimus amount, usually around $25,000. The result is the sponsor gets 20% ownership in the SPAC for virtually free.

Phase 2: Merger Target Search and Due Diligence

Once the IPO is complete the second stage begins, the sponsor looks for a private company to merge with before the two-year deadline to complete a merger comes to an end. The sponsor must both identify a company and complete a merger within two years, or the SPAC will be unwound, and the money raised in the SPAC IPO will be returned to investors usually at the $10 initial offering price plus any accrued interest from the securities held in the trust.

When the sponsor has identified a merger target, they perform their due diligence on the target company and negotiate the terms of the merger. When a non-binding purchase agreement has been drawn up, the sponsor will publicly announce the merger. If the cash to be paid in the merger exceeds the amount of cash in the SPAC trust, then the sponsor will raise more money through a private investment in a public equity, or PIPE transaction.

A PIPE transaction sells additional shares of the SPAC to a select group of accredited investors, usually institutional investors, hedge funds and mutual funds. Investors in the PIPE are usually given more favorable terms including the opportunity to buy shares at a discount to the IPO price and access to material non-public information about the merger details.

Finally, after shareholders are given details of the merger, they may decide to hold their shares through the merger or put them back to the SPAC, requiring the SPAC to repurchase their shares from them. Importantly, investors in the IPO are permitted to keep the rights and warrants they received, even if they sell their shares back.

Phase 3: Merger and De-SPACing

The last phase is to close the on the merger and merge the SPAC with the target company. The target company issues shares to the SPAC investors in exchange for the money raised by the SPAC. The SPAC becomes a normal operating company with the financial and business history of the target company. The target company is now a public company with newly raised capital received in the merger and the SPAC shareholders become minority shareholders in the target company. The final ownership percentage the SPAC shareholders have in the newly public target company depends on how much money was delivered during the merger.

What’s in it for me?

The best way to understand structured finance deals is to examine them from the vantage point of the parties involved. Investing is not a charitable pursuit, to understand complex financial deals you have to understand what each party stands to gain or lose in the deal. There are three main parties in a SPAC deal, the sponsor, the investors in the SPAC, and the target private company and its shareholders that will ultimately merge with the SPAC.

The Sponsor

How does the sponsor stand to benefit from managing a SPAC? Easy, money…potentially a lot of money with very little of their own capital at risk.

If you recall, after the IPO the SPAC sponsor receives a ‘promote’ and retains 20% ownership of the SPAC for nearly free. If the sponsor successfully completes a merger regardless of the quality of the target company or its long-term prospects of success, the sponsor will earn a windfall by owning a substantial share of the newly public target company. Even if the price of the newly public target company falls significantly after the merger, which is common, the sponsor, who received their shares for nearly free will have substantial gains.

The sponsor’s role highlights the biggest problems with SPACs, the sponsor’s interests do not align with interests of SPAC investors. The only way for the sponsor to have an economic loss is if they fail to complete a merger within the allotted time. Therefore, the incentive for sponsors to complete a deal regardless of the quality of the target company or fail to negotiate favorable terms for the SPAC investors is huge. Even the worst merger deal imaginable will likely reap millions or tens of millions of dollars in rewards for the sponsor.

The Target Company

Private companies needing to raise capital may be interested in merging with a SPAC for a variety of reasons. One advantage of merging with a SPAC instead of having an IPO is that a SPAC merger may be quicker than an IPO, therefore getting needed capital to the company faster and with less hoops to jump through.

Traditional IPO’s require companies to convince perhaps hundreds of sophisticated investors that their business has strong future growth prospects and that the company is being valued correctly prior to the IPO. Merging with a SPAC requires companies to convince only one investor (the sponsor) of their future business prospects and given the massive incentives that accrue to the sponsor if a merger is completed, companies needing capital have a very receptive audience.

A disadvantage to a private company looking to merge with a SPAC is that the amount of money that will ultimately be delivered in the merger with a SPAC is uncertain. Investors have the option to put their shares back to the sponsor prior to the merger leading to uncertainty in the final amount of capital that will be raised.

SPAC investors need to be aware that a company looking to raise capital and go public through a SPAC merger may be doing so because they do not have any other options. A company’s options for raising capital can be limited if the business is complex, has poor financial performance, limited operating and financial history or poor future growth prospects. Investors are trusting the sponsor to do the due diligence and negotiate a fair valuation, however as we have covered, their financial incentives are more aligned with the target company than those of the SPAC investors.

The SPAC Investor

There are two groups of SPAC investors, the initial SPAC IPO investors and investors who buy shares of a SPAC in the open market after the IPO. Like any IPO, the initial investors are usually institutions and hedge funds. This is important because SPACs are often described as ‘democratizing private equity’ by giving individual investors the opportunity to participate in pre-IPO deals that they generally would be excluded from participating in. While this is true regarding the eventual merger of the SPAC with a target private company, it is not true in regard to the IPO of the SPAC itself.

The reality is that individual investors do not generally get an allocation to SPAC IPO shares but can only buy them in the open market post-IPO, which puts them at a great disadvantage to institutional IPO investors. Importantly, each SPAC IPO share comes with a free, detachable warrant that the IPO investor gets to keep even if they redeem or sell their shares prior to the merger, shares purchased in the open market do not have the warrant attached.

Okay, for the individual investors out there, let’s get to the heart of the issue with SPACs and why you should probably play in a different sandbox. Exclusion from the SPAC IPO shares and attached rights and warrants, information disadvantages, and massive hidden expenses makes any investor buying SPAC shares in the open market the designated bag holder, or the sucker at the poker table. Investors that hold their SPAC shares through the merger are the ones subsidizing the high cost of the SPAC IPO benefiting the target company and pays the outrageous ‘promote’ costs in the form of 20% of the SPAC ownership the sponsor receives for virtually free.

It might surprise you that according to a study of SPAC transactions between January 2019 and June 2020 the average return for a SPAC IPO investor was 11.6% and the mean return of a SPAC twelve months after a merger was -34.9%[i]. So individual investors that buy SPAC shares in the open market and hold them for a year after the merger would have, on average, lost at least a third of their money assuming they bought the SPAC shares at the IPO price of $10 and did not pay a premium to the IPO price making their return even lower.

Why is it that most hedge funds and institutional investors in SPAC IPOs do so well and shoulder minimal to no risk and SPAC investors that hold through the merger shoulder all the risk and do so poorly? It is because of the inherent advantage that IPO investors gain from the attached rights and warrants, their information advantage and because of shareholder dilution that is built into the SPAC structure.

Rights and Warrants

Most SPAC IPO shares are sold to a contingent of hedge funds that specialize in SPAC arbitrage. Here is how it works. They buy shares in SPACs at the IPO and receive the shares at the unit price of $10 as well as the attached rights and warrants. Here is the catch, these investors have no plans to stick around for the eventual merger. Because of their advantage of buying shares of the SPAC at the IPO price of $10 and receiving the attached rights and warrants that they get to keep even if they sell or redeem their SPAC shares, their strategy is to earn essentially risk-free double-digit returns. Here is how the strategy works.

After the SPAC IPO, if shares of the SPAC trade at a premium to the IPO price of $10, IPO investors can simply divest their shares in the SPAC by selling their shares on the open market to individual investors for a gain while keeping their free rights and warrants. If they do not sell their shares in the market, then they can put them back to the SPAC prior to the merger and receive their initial investment plus interest and hold onto the rights and warrants. Once the merger has been completed, if the price of the newly public company stock rise over time, they can exercise their rights and warrants and receive discounted shares of the public company for a risk free gain.

The little guy gets diluted

Now let’s look at what happens to investors that do not have rights or warrants and bought their shares in the SPAC pre-merger and hold them through the merger. These investors subsidize the underwriting fees and massive compensation of the sponsor by having their share of ownership of the target company post-merger severely diluted. Dilution occurs when shareholders equity or ownership percentage is decreased through the issuance or creation of new shares. Dilution in SPACs are a massive hidden expense that should never be ignored by investors. The success of SPAC deals and the compensation of the sponsors count on a group of investors being indifferent or just not understanding dilution.

There are three sources of dilution that SPAC shareholders face post-merger, the sponsor ‘promote’, underwriting fees and the exercising of outstanding warrants. The sponsor ‘promote’ is easy to understand as they are given essentially free shares that added no additional cash to the SPAC trust, so the promote shares naturally dilute the SPAC investors’ ownership percentage in the post-merger company.

Less obvious is how underwriting fees for the SPAC IPO dilute SPAC investors. Like any traditional IPO, a SPAC sponsor hires an underwriter to take the shell company public to raise assets. The standard underwriting fee for a SPAC IPO is around 5.5% of the total equity raised. Around 3.5% of that fee is usually deferred and conditioned on a merger being completed.

However, greater than 50% of SPAC shares are usually redeemed prior to a merger, but the underwriting fee is not adjusted and is still paid as a percentage of total asset raised in the initial SPAC IPO. If 50% of the SPAC shares redeem prior to the merger then the effective fee calculated as a percentage of cash delivered to the merger target is 11% not 5.5%. The ownership percentage the SPAC investors will have post-merger is a function of how much cash is delivered to purchase shares of the target company, the target company does not foot the underwriting bill but instead the SPAC shareholders do through a lower percentage of ownership of the target company.

Finally, rights and warrant are clearly dilutive because if the share price of the post-merger company rises, the holders of the rights and warrants are likely to exercise their free option to buy discounted shares, new shares are then created, and SPAC shareholders are diluted. The dilution from rights and warrants can be severe and the extent to which SPAC shareholders can be diluted increases with pre-merger redemptions.

Let’s break this down. Initial investors in a SPAC receive a warrant with each share they purchase at the IPO. If 50% of these initial investors redeem there shares prior to the merger they get to keep the warrants. After the merger the original number of warrants are still outstanding, however the number of units and therefore cash delivered in the merger has been cut in half therefore doubling the dilutive effect on the remaining SPAC shareholders.

The same study I referenced earlier found that total costs for the median SPAC transaction between January of 2019 and June of 2020 that is passed on to SPAC shareholders that held shares through the merger was a breathtaking 50.4%![1]

If we are being honest, what other result should we expect

from an investment structure that is billed by Wall Street as ‘democratizing

private equity’. SPACs are the typical big finance shell game where huge

financial windfalls can be made, but not without a sucker. My advice, don’t be

the sucker.

[i] Klausner, Michael D. and Ohlrogge, Michael and Ruan, Emily, A Sober Look at SPACs (October 28, 2020). Yale Journal on Regulation, Forthcoming, Stanford Law and Economics Olin Working Paper No. 559, NYU Law and Economics Research Paper No. 20-48, European Corporate Governance Institute – Finance Working Paper No. 746/2021, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3720919 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3720919